Unraveling the Philosophy of Life: Insights from Eastern Wisdom

Borzou Ghaderi

Abstract: This article presents a comprehensive exploration of the structure of suffering and the quest for liberation within the context of Eastern philosophy. Drawing from the profound insights of Samkhya and Yoga traditions, it investigates the intricate subject-object duality, highlighting the five fundamental causes of suffering (Pancha Klesha) that intertwine and perpetuate restlessness and unfulfilled desires. The paper further elucidates the concept of “enstasy” as a path to liberation, offering moments of profound detachment and unity with intrinsic truth. Ultimately, it emphasizes that the eternal quest for meaning is a deeply personal journey, guided by Eastern wisdom, to uncover profound meaning within the depths of human consciousness.

Keywords: Eastern philosophy; Samkhya; Yoga; Pancha Klesha

I. Introduction

In the grand tapestry of human history, the quest to unravel the intricate threads of life’s philosophy and meaning has captivated the minds of thinkers and philosophers across diverse cultures and philosophical traditions. As we delve into the annals of human existence, it becomes evident that humanity has perpetually grappled with a multitude of challenges and adversities.

In ages long past, the foremost fears that haunted humanity were the specters of wild animal attacks, the gnawing pangs of hunger and thirst, and the capricious wrath of natural disasters. However, as civilization advanced, these primal fears gradually gave way to more contemporary concerns—employment, social competition, and the intricacies of familial relationships. Yet, beneath the ever-shifting nature of these challenges, the perennial quest for fulfillment and happiness remains a constant.

Eastern traditions, steeped in profound wisdom and teachings, offer invaluable insights into this eternal quest for meaning and purpose in life, transcending temporal and cultural boundaries. In this article, we shall embark on a journey deep into the recesses of the human psyche, drawing inspiration from the sagacious works of Eastern sages and philosophers. Through this exploration, we will endeavor to understand the concept of life’s meaning through the unique lens of Eastern traditions.

II. A Psychological and Philosophical Odyssey

Human challenges can be broadly categorized into two main domains, each of which has given rise to distinct strategies throughout human history. Some of these challenges relate to the maintenance of stability in our external lives. In the modern era, characterized by the fruits of the scientific revolution, we have achieved unprecedented progress in meeting our material and external needs. Another set of challenges pertains to the apprehension of death, the quest for life’s meaning, and the pursuit of inner peace.

In essence, humans have perennially traversed two paths in their quest for happiness and well-being: the outer path, often referred to as the “objective path,” which secures material security, and the inner path, often dubbed the “subjective path,” dedicated to attaining inner peace and happiness. While Western civilization has made remarkable strides in harnessing the material potentials of nature, Eastern philosophies have unearthed profound insights into the meaning of existence and practical solutions for human happiness and inner serenity.

In this discourse, we shall focus on the second path—the “psychic way.” We shall delve into the teachings of Eastern wisdom, aiming to provoke profound questions and contemplation, offering inspiration for our philosophical inquiries.

III. Duality of Subject and Object

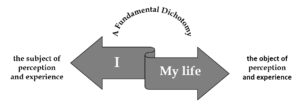

In our exploration of the inner self, we encounter a fundamental dichotomy: the “I” as the subject or agent of perception and experience, and “my life and dreams” as the object of perception and experience. The theme of life and its meaning revolves around the connection and interaction between this subject and object (Fig. 1).

This interaction has the potential to engender peace, joy, and profound motivation through the projection of the subject onto the object. It is this very connection that imbues human life with color and meaning; any disruption in the interaction between subject and object threatens to render life devoid of meaning.

To illustrate this concept, consider the following scenario: envision an individual highly driven to excel in their chosen field of work. This person dedicates themselves to honing their knowledge and skills, fueled by the aspiration to reach the pinnacle of their career and seize greater opportunities. In this context, a robust and profound connection forms between “them” as the subject and “their work” as the object. This deep bond ignites their motivation, propelling them forward in the pursuit of their career aspirations. It is, at this juncture, that they may genuinely claim to have discovered meaning in their life. However, what transpires when this individual does indeed ascend to the zenith of their profession? This accomplishment, paradoxically, disrupts the critical interaction between subject and object. The once-potent motivator loses its vigor, and a sense of meaning dissipates. In such moments, individuals often grapple with inner turmoil until they manage to establish new connections with different objects and effectively engage with them.

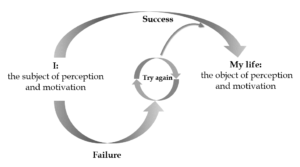

When delving into the profound question of life’s meaning, we must realize the fundamental equation at play: one side comprises “I,” representing the subject of perception and motivation, while the other side encompasses “my life,” representing the object of perception and motivation. This object, “my life,” manifests in various dimensions and levels. It is the interaction between oneself and life itself that imparts meaning to existence, motivating individuals to pursue a multitude of goals and objectives. This very motivation, in turn, breathes life into existence, imbuing it with profound meaning.

However, from this point, we encounter two distinct states: firstly, the incapacity to interact effectively with life’s circumstances, leading to a sense of frustration; secondly, the ability to adeptly engage with life’s challenges and realize ambitions through personal will (Fig. 2). Yet, even in the latter scenario, a fundamental question persists: what comes next? Surprisingly, many highly accomplished individuals have found themselves in a state of emptiness and absurdity upon reaching the zenith of success. It’s as if life’s meaning fades into oblivion once ambitions are fulfilled, leaving an existential void. This situation prompts a crucial question: Can individuals continue to find meaning in life and construct new narratives even after scaling the peaks of success?

The answer to this existential question lies in comprehending the intrinsic dualism between subject and object. The subject, often referred to as the “essence” in Sufi mysticism1 and Purusha in Vedic teachings2-7, remains an enigmatic facet of human nature. While many philosophical schools have ventured to probe this essence, a definitive understanding remains elusive. However, by observing its projections onto the surrounding world, we can begin to grasp the facets of this enigma. Just as an artist’s creations reflect their personality and life experiences, a study of our ideas, desires, and motivations can shed light on the nature of the subject.

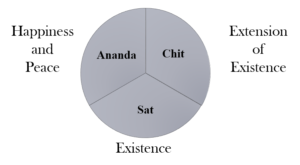

The origins of these myriad desires and motivations warrant exploration. According to Vedic teachings, humans possess three fundamental and intrinsic motivations: the will to survive and exert power, the will to enhance their existential position, and the will to derive pleasure from their achievements. These principles, known as Sat (existence), Chit (development of existence), and Ananda (happiness and peace)8, resonate in Iranian Sufi literature, where they are interpreted as existence, wisdom, and love1 (Fig. 3).

In the realm of wholeness, where the root of consciousness resides, these three principles meld into absolute unity, transcending duality between subject and object, mind and matter. It is a state of profound peace, joy, and serenity, termed Sat Chit Ananda in Vedic teachings, akin to the state of infancy or deep dreamless sleep, is devoid of choice, desire, or denial. Here, life’s manifestations and challenges find no foothold. Reflecting deeply on this concept offers a unique perspective on the interplay between subject, object, and the gap that separates them.

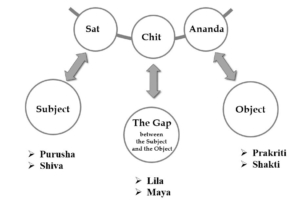

In Eastern spiritual literature, this duality of subject and object is a recurring theme, articulated through various terms such as Purusha and Prakriti2-7, Shiva and Shakti9, and the enigmatic concept of Maya10.

This intrinsic dualism forms the foundation of our narratives, shaping the course and direction of our lives. As we journey through existence, we navigate the chasm that separates the subject from the object, endeavoring to bring them into harmony. The interplay between subject and object defines the narrative of our lives—a narrative that encompasses both the challenges and triumphs, the aspirations and achievements.

In essence, the duality of subject and object is the essence of human existence itself. In the rich tapestry of Eastern philosophy, this profound concept serves as a guiding light on our quest to unveil the mysteries of existence and find meaning in the intricate dance between the self and the world.

IV. Unveiling the Essence of Sat Chit Ananda in the Trinity of Subject, Object, and the Abyss Between Them

Delving deep into the enigmatic realm of Eastern philosophy, we uncover a profound understanding of the subject, object, and the intricate gap that binds them together, a notion intricately woven into the tapestry of Sat Chit Ananda.

In this profound dichotomy, the subject occupies one facet—an embodiment of pure existence and presence, echoing the Sat principle. In the narratives of Yoga and Samkhya literature, this sheer presence is referred to as Purusha2-7. Tantra’s perspective labels it as the essence of Shiva9. On the opposing end of this duality, a myriad of ambitions manifest as life’s objects, igniting our desires and motivations to approach and attain them. These objects resonate with the essence of Ananda, for they promise joy and profound peace upon their attainment. Samkhya and Yoga literature characterize this principle as Prakriti, representing the primal urge for action2-7. In Tantra, it goes by the name Shakti9. When the “I” assumes the role of Purusha, the subject, a tapestry of life’s issues within the “I’s” living milieu transforms into objects, propelled by the “I’s” determination, desires, willpower, and vital force, all striving for acquisition or avoidance.

At the heart of this mystical narrative lies the space where the mythological geography of human existence unfurls—the chasm between the subject and their yearning for peace and happiness. This void, seen through the lens of the Chit principle, assumes various facets depending on the dimension the object represents within the subject’s life. Challenges of multifarious nature emerge in this gap, shaping the journey to reach the object. This abyss between subject and object takes on names such as Lila, signifying cosmic play and tribulations in the Vaishnava Sampradaya School10. Another evocative term, Maya, alludes to the mirage-like illusion that separates the subject from the object. To grasp the essence of this fundamental duality, we must embrace the notion of Maya10, which reminds us that subject and object share a fundamental unity. The perceived division between them is, in essence, illusory, and Maya stands as the dominant-negative force in this paradigm (Fig. 4).

Nonetheless, it becomes apparent that these three principles—the subject, object, and the gap between them—struggle to manifest fully in the realm of human life. Factors such as time and the constraints of a world filled with multiplicity perpetually obstruct the convergence of these principles. As mentioned earlier, they attain unity solely in the state of deep dreamless sleep, known as Sat Chit Ananda in Upanishadic terminology. Sufi literature parallels this realm with the concept of the “inner self” 1. Here, “inside” denotes the dream world, while the “inside of human inner” represents the realm of deep sleep or rationality—the realm where perpetual inner peace resides. This domain is free from the dualism that plagues the conscious world. As humans descend from inner stillness into the realm of self-awareness, the three principles of Sat Chit Ananda fragment and drift apart.

V. Subject, Object, and Their Interaction in Different Terminologies

As the core of self-consciousness, the subject ceaselessly seeks oneness with diverse objects, reflecting humanity’s quest to actualize the ideas residing within their psyche. These ideas, bestowed with unique names in different cultures and languages, embody the very Devas and Devatas in Tantra culture10, or the fixed entities in Ibn Arabi’s mystical terms11. They also bear a resemblance to the collective unconscious archetypes central to Carl Gustav Jung’s theories.

Within the spectrum of this subject-object duality, nothing remains constant; every element is in perpetual flux. Roles are transient, a fact epitomized by the Maya spectrum’s characterization as a ceaseless game (Lila), where roles continuously evolve. The quintessential question arises: Why engage in this cosmic play at all?

The ancient wisdom of the East provides an answer—a journey of self-consciousness, designed to enable us to inhabit the roles of ancient Devas and Devatas within our conscious lives. This transformation allows us to unlock our full potential, becoming self-aware across the entirety of life’s vast spectrum of experiences and challenges. This concept finds expression as “the perfect man” in the doctrines of Muslim mysticism11.

The object, in essence, is the very essence of man’s existence and nature—the canvas upon which the human will project itself. These domains and levels of awareness each possess distinct and unique characteristics, adding depth and complexity to the human experience.

VI. The Circle of Human Experiences Allegory

In the vast landscape of Eastern philosophy, the essence of human existence is explored as a profound amalgamation of personal and collective perceptions and experiences. This perspective allows us to delve into the very core of our being, granting us ontological and existential self-awareness—a remarkable facet that distinguishes us from other creatures inhabiting our shared world. It is this self-awareness that elevates humanity to a unique and superior position in the grand tapestry of existence.

To grasp the depth of this insight, imagine human experiences as points within an expansive circle—a circle that embodies the absolute essence of humankind, transcending the boundaries of any individual. This circle represents the full spectrum of possible human experiences, an array as diverse and intricate as the facets of a multifaceted gem. Within this circle lie the desires for freedom, love, tranquility, pride, despair, and a myriad of other phenomena, each a unique point within this tapestry. Some of these experiences may resonate with each of us, while others remain uncharted territory.

Consider, for instance, the profound and consuming love of Romeo or the destructive jealousy of Othello. These experiences represent just a few of the countless facets within the human psyche, a tapestry so intricate that it stretches beyond our immediate comprehension. In the vast expanse of human consciousness, we encounter a plethora of experiences, some of which may remain hidden in the depths of our being. It is undeniable that those who have managed to traverse a wider swath of this circle possess a more profound and mature understanding of the human spirit. They have ventured into the uncharted territories of the human psyche, exploring the full spectrum of its dimensions (Fig. 5).

This circle encompasses both the dark and bright dimensions of the human psyche—a subject of perpetual contemplation and debate. Islamic Sufi literature, for instance, has occasionally extolled the figure of Satan as a source of learning—not in the dark and malevolent sense but as an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the shadowy recesses of our psyche.

The circle, however, is not merely an assemblage of hypothetical points; it operates under certain rules that govern the connections between these points. These rules find expression in Oriental mystical literature through terms like “fixed entities” or “divine names and qualities”11. In modern parlance, they may be considered archetypal forms capable of transforming concepts and values, giving rise to new structures.

For instance, the mother archetype may imbue self-sacrifice and suffering with great value for the sake of one’s children, equating it with merit. In contrast, the hero archetype sacrifices not for progeny but for the courage to confront darkness and adversaries. Literature throughout history has often been written during times of personal struggle, suggesting that life’s chaos grants access to a broader spectrum of experiences. However, this journey into the unknown, from safe havens to uncharted territories, is often fraught with grief and pain.

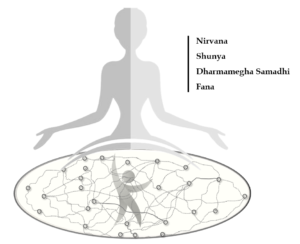

Here, a critical point emerges. The colossal circle of human experiences, shrouded in obscurity for many, is a territory that certain Oriental sages have sought to transcend. Only a select few, like Buddha Gautama, have claimed to achieve this feat, whether this transcendence was literal or metaphorical remains a subject of debate. Across the annals of Eastern mysticism, various terms have been employed to describe this experience of transcendence. The Buddha introduced the concept of Nirvana, while Zen teachings explored Shunya10. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras referenced Dharmamegha Samadhi12, and Muslim Sufis contemplated Fana1. Yet, the question of whether these wise individuals indeed crossed this metaphysical circle is not our focus today, for logically, such a feat would appear inconceivable (Fig. 6).

Our exploration delves into why these luminaries contemplated departing from this vast and captivating circle of human experience—a realm that is at times enchanting and at times disheartening. What characteristics does the human experience, or the experience of being human, possess that led many Eastern sages to consider leaving this circle behind? What understanding within their psyche left them disillusioned with continuing their journey in this realm yet hopeful of embracing a realm devoid of both suffering and happiness? Moreover, why did the vibrant world regain its significance for them, transforming into a manifestation of blessings and wisdom when they ventured into the realm of colorlessness?

In the realm of Eastern philosophy, these questions form the crux of a profound journey—a journey into the heart of human existence, perception, and transcendence.

VII. Unveiling the Cosmic Matrix: An Exploration of Prakriti in Eastern Philosophy

In the realm of Eastern philosophy, there exists a profound concept, a cosmic matrix referred to as Prakriti in Vedic tradition. Prakriti, this intricate cosmic web, entwines us within the structure of human existence, bearing witness to experiences that resonate with each of us. As sages of the Orient have illuminated, the realm of human experiences is characterized by three fundamental properties: Anitia, signifying variability; Anatma, suggesting the absence of a fixed identity; and Dukkha, the embodiment of suffering, which is inextricably linked to the preceding two properties10.

Anitia: The Ever-Changing Nature

The principle of Anitia underscores the ceaseless transformations that define the universe. No structure within the canvas of life, be it our physical form or intellectual constructs, can maintain unyielding stability. For instance, one can fervently devote attention to the body’s well-being and bolster the will to elevate physical standards. Diligent efforts might yield tangible changes in physical capabilities and levels of satisfaction. However, the body’s constancy remains elusive, as the inexorable passage of time inexorably ushers in the changes associated with aging. This relentless motion is mirrored in the term Jahan in Persian literature, rooted in the word Jahidan, signifying movement and oscillation.

This never-ending transformation is not limited to the human body alone. Throughout history, individuals who have influenced countless others with their thoughts and intellectual palaces have themselves undergone profound shifts in beliefs. The life of St. Augustine stands as a poignant example, with his convictions undergoing recurrent transformations. Such intellectual malleability is not uncommon; thinkers like Ludwig Wittgenstein underwent remarkable intellectual metamorphoses during their lifetimes. In essence, the first characteristic of the realm of perception and life, articulated by the Buddha as Anitha in Sanskrit literature and Anicha in the Pali language, is its perpetual mutability.

Anatma: The Absence of a Fixed Identity

Another defining attribute of existence lies in the concept of Anatma—the absence of a fixed and eternal identity. In this intricate web of life, neither our mental constructs nor our living environments possess an enduring essence. The flux within our surroundings inevitably triggers shifts in our roles and positions. Life resists the notion of an unchanging self.

To illustrate this, imagine residing in a house within a village. At one point, you played the role of a child within that household, your father being the head. Over time, circumstances transformed, and you assumed a pivotal role, becoming the decision-maker. Eventually, you will transition into the role of a grandparent, passing on your managerial responsibilities to the next generation. Life recognizes no static ego. Each of us engages in a complex dance with nature and existence, and as the grand machinery of life undergoes alterations, so do our roles as agents of will.

Throughout the rich tapestry of Iranian Sufi literature, the theme of the world’s transience has been a perennial subject of contemplation. One such tale that resonates deeply with this theme involves the transformative encounter between Ibrahim Adham, the ruler of Balkh, and the enigmatic Khidr.

Ibrahim Adham, who would later become one of the eminent Sufis of his era, found himself within the opulent confines of his royal palace in Balkh. One day, an extraordinary encounter unfolded before him as Khidr, the mythical guide and seeker of wisdom, appeared in the guise of a cameleer. Khidr, in his unassuming demeanor, expressed a simple request: “I wish to spend a night in this caravanserai.”

However, Ibrahim Adham, accustomed to the splendor of his palace, responded with a courteous but bemused tone, “This is a royal palace, not an inn.” Little did he know that this encounter would unravel the very fabric of his understanding of existence.

Khidr, undeterred, continued his gentle inquiry, probing the depths of Ibrahim Adham’s awareness: “Who sat upon this illustrious throne before you?” To this, the ruler replied, “My father graced this throne with his presence.” Khidr persisted, inquiring further, “And who sat here before your father?” Ibrahim Adham’s response revealed a lineage of predecessors: “My ancestors, for generations.”

The conversation reached its zenith as Khidr delved into the annals of history, inquiring about those who had assumed the mantle of leadership in the palace. Finally, he delivered a profound revelation: “This is the essence of the caravanserai. If you, as the king, seek to understand its true nature, know that it is not a permanent residence for anyone.”

In this mesmerizing encounter, Ibrahim Adham’s realization mirrored a profound truth that echoes through Eastern philosophy and Sufi wisdom—the impermanence of the world and the transitory nature of all that we hold dear. The palace, once a symbol of power and permanence, unveiled itself as but a fleeting resting place in the grand journey of existence.

Dukkha: The Realm of Suffering

It is at this juncture that the concept of Dukkha emerges in Eastern mystical literature—a term rich with meaning. Dukkha comprises two components: Do, signifying two, and Akash, denoting ether or space. In essence, Dukkha conveys the existence of a void or gap between two entities. These entities, in the deepest sense, symbolize the duality between subject and object—a gap that persists in perpetuity within this life. Eastern sages perceived this supposed circle of human experiences as intricately tied to Dukkha or suffering. However, this suffering transcends mundane trials and tribulations; it represents an abstract concept intricately interwoven with the very mechanics of human existence.

As we delve deeper into the nature of suffering, we must ascertain where, within the realm of the human psyche and experience, this suffering takes root. The foundational duality between subject and object comes to the fore. This duality is the crucible within which suffering is formed. The object, or that which is perceived, bears inherent imperfections—it is subject to perpetual change and instability. Simultaneously, the subject, the agent of perception and cognition, harbors lofty and abstract aspirations. These aspirations transcend the ephemeral nature of the world, extending into the realms of survival, knowledge, and happiness. These intrinsic ambitions, deeply etched in the human psyche, are rooted not in the ego but in the collective human consciousness. The subject endeavors to realize these ambitions within a world defined by temporal and spatial limitations. Thus, suffering arises from the dissonance between these absolute needs and ambitions and the confines of the physical world.

The human psyche yearns for an elusive sense of fulfillment, seeking to satiate desires that transcend the limitations of existence. Yet, these pursuits oscillate between two states: either entering an endless cycle of unfulfilled needs, intensifying restlessness, or momentarily experiencing satisfaction only to realize that it fails to quell the innate restlessness. This intrinsic human longing for the absolute grapples with a world inherently incapable of providing absolute fulfillment. Thus, the essence of human identity appears restless, refusing to be confined within the boundaries of the changing world.

VIII. The Abstract Structure of Suffering: Pancha Klesha

In the tapestry of Eastern philosophy, an intricate understanding of suffering permeates the wisdom imparted by sages of ancient traditions. This discourse delves into the profound concept of suffering as comprehended by these luminaries, along with the methods they proffered to transcend it.

Within the human psyche, the structure of suffering reveals itself as an intricate abstraction. Eastern schools and traditions assert that this intricate framework persists until the very subject, the agent of perception and cognition, undergoes a profound transformation.

As previously alluded to, suffering is rooted in a fundamental duality—a duality that manifests as the “I” on one side and the objects of perception, experience, and sensation on the other. The crucial question at this juncture is this: where does suffering find its dwelling within this duality?

We’ve discussed the inherent imperfections of the objects we perceive; They are in a constant state of flux, incapable of offering us stable and definitive states. Take, for example, the human body—an entity subject to the relentless march of time, inevitably succumbing to the changes of aging. This impermanence extends beyond the physical realm, penetrating the very core of our beliefs and convictions. Throughout history, individuals, even great thinkers like St. Augustine or Ludwig Wittgenstein, have witnessed their ideologies evolve and transform over time. This ever-changing nature is a universal phenomenon, evident in all aspects of existence.

However, Eastern philosophy posits that the source of suffering extends beyond the imperfections of objects. It delves into the depths of human consciousness, unearthing profound, timeless, and abstract aspirations. These aspirations, more profound than the ego, reside in the essence of human nature, relentlessly urging the pursuit of completeness. These innate ambitions—the will to exist and survive, the will to expand and acquire knowledge, the will to experience happiness and love—are deeply embedded within the human psyche. However, when projected onto a finite and ever-shifting world, these absolute desires remain unfulfilled, leaving the human soul restless.

Looking beyond the apparent limitations of external objects, one discerns that the subject itself—the agent of perception—holds a more elevated position than the perpetually shifting world it encounters. In simpler terms, the human psyche appears to possess authenticity and nobility, yet it inhabits a world that falls short of its inherent dignity. Therefore, as one traverses this universe, a sense of restlessness ensues, possibly even descending into profound despondency. It becomes evident that the mechanisms of this world are intrinsically ill-suited to wholly satisfy the absolute needs of the human psyche.

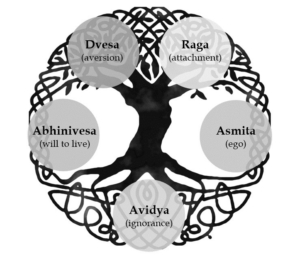

Within Eastern traditions, an illuminating analysis of suffering emerges from ancient texts such as the Yoga Sutras, which delineate the five causes of suffering, collectively termed Pancha Klesha in Sanskrit literature12. These five causes are Avidya, signifying ignorance; Asmita, representing ego; Raga, denoting attachment; Dvesha, indicating aversion; and Abhinivesha, translating to the will to live.

According to the Yoga Sutras, these five causes of suffering intricately interweave with one another and are entirely interdependent. In essence, there is a profound underlying structure responsible for the human experience of suffering, a structure that warrants deeper exploration.

It commences with Avidya or ignorance12. In Sanskrit, Vid conveys the idea of knowledge, while Avidya suggests the absence of knowledge. The ignorance referred to here is born from the interaction between the subject and the object. In simpler terms, it arises when a subject, consumed by absolute concerns, exists within a world marked by numerous limitations. Despite these constraints, the subject endeavors to fulfill its absolute needs within this ever-changing world. Consequently, from the perspective of the Yoga Sutra, it all begins with ignorance, a byproduct of the interplay between subject and object. This connection essentially gives rise to suffering, since the subject pursues absolute demands unattainable within this realm. To put it differently, the profound desire for survival and immortality, the quest for ultimate wisdom and knowledge, and the pursuit of boundless happiness and blessings represent absolute concerns that can never find fulfillment within the confines of a limited world. Thus, the interaction between subject and object primarily results from Avidya or ignorance. The world we inhabit is not one of absolutes but rather a world characterized by constant variability. Our endeavors to satisfy our fundamental needs – survival, knowledge, and happiness – are subject to two possible outcomes. We either engage in a cycle that cannot fulfill these needs, intensifying our restlessness, or we find ourselves in an interaction capable of meeting these needs and ambitions, only to realize that our restless nature remains unquenched by such fulfillment. When we fail to attain our desires, we redirect our efforts towards meeting other needs, projecting our ambitions onto different matters and channeling our energy accordingly. Ironically, more prosperous societies, often considered unhappier, grapple with more intricate philosophical concerns. They recognize that even when their basic needs and ambitions are met, a profound sense of fulfillment remains elusive. Thus, the foundation of suffering, as discussed thus far, emerges from Avidya or ignorance, stemming from the very nature of the interaction between subject and object. Such ignorance, regarding our absolute needs and the inherent constraints of the natural world, immerses us in a state of suffering.

In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, the second of the five causes of suffering is Asmita or the concept of “I am-ness” 12. Asmita represents what we project as our identity, arising from a particular mechanism between our inner desires and our external environment. Consequently, the subject itself can exacerbate its internal suffering. As long as the “I,” serving as the agent of perception and experience, believes it can fulfill its absolute ambitions within the world of plurality, it remains trapped in a relentless cycle. This conviction persists as long as the “I” is perceived as both the perceiver and the experiencer. However, when we distance ourselves from the universe, viewing ourselves as the “I,” and strive to fulfill the needs and desires of this “I” within the realms of the mind, intellect, or nature, a potential for inharmoniousness is involved because the “I” erroneously considers itself separate from nature.

We often seek to gratify desires that do not necessarily align with the reality of the environment in which we find ourselves. The fulfillment of these absolute needs can only occur within the constraints of time and space. This fulfillment can lead to enthusiasm and attachment, giving rise to the concept of Raga, yet another cause of suffering. Conversely, the inability to fulfill these needs results in Dvesha, or aversion, representing yet another source of suffering12. However, attachment and aversion are two sides of the same coin, as these pleasures eventually wane with the emergence of new needs and ambitions. All the sorrows and joys are eclipsed by the pursuit of new objectives. In essence, the desire and thirst for living within the narratives of life, termed Abhinivesa12, sustain this perpetual cycle. Human existence is marked by numerous disappointments. Millennia of human history attests that manipulating external objects and attaining them can never truly bestow genuine happiness upon the human psyche or alleviate the inherent restlessness within. It appears that humanity remains ensnared in this cycle of perpetual disappointment. As previously emphasized, the root of these disappointments can be traced back to a fundamental dichotomy: on one side lies a restless, absolutist psyche, while on the other rests a finite, restricted, and constrained world fundamentally incapable of satisfying these absolute needs and aspirations. Consequently, the narrative of human life and its interaction with the world perpetually unfolds in the shadow of suffering (Fig. 7).

XI. Enstasy: Liberation from Suffering

In Eastern traditions, a compelling solution emerges to liberate oneself from the ceaseless cycle of suffering, known as Samadhi or enstasy in Sutra literature12. This concept underscores the suspension of the subject’s connection to external objects, enabling a momentary detachment from the perpetual unity with external phenomena. Within these fleeting moments, individuals can experience an existential comprehension that transcends verbal expression.

Those who undergo this existential experience come to a profound realization—namely, that the myriad dreams projected onto various objects ultimately mirror the essence of their existence in its most abstract form. In essence, while individuals, as agents and subjects of perception, seek countless objects to fulfill their desires, ambitions, and dreams, they discover that behind these pursuits lie abstract and fundamental needs that reveal the very reality of the subject itself.

In this perspective, the subject and the object are not independent entities; they form a singular reality, and this is one of the central tenets of mystical philosophies. In Vedanta, it is said that Purusha, Prana, or Prakriti, is indeed Brahman. In other words, it is declared that “I am that” or “tát tvam ási,” signifying that the essence of the subject is synonymous with the ultimate reality13,14. Similarly, among Sufis, we witness this concept conveyed through profoundly moving expressions, with the underlying message being that the truth of the self is found in unity with the diverse phenomena of the world10. It essentially posits that our reality inherently aligns with our projections. In other words, as the human psyche seeks to alleviate its concerns through the pursuit of transient and ever-changing ambitions, it can unearth its fundamental truth in the process.

Consider the analogy of a painter—although we may not discern the essence of the artist’s spirit, we can discern it through their artwork. Similarly, despite the nebulous nature of the subject, one can grasp their reality and essence through their intentions and actions, encapsulated as Sat Chit Ananda. At birth, we project this three-dimensional reality into a world of variables, striving to regain “Sat Chit Ananda“—a sense of establishment, awareness, and tranquility—within the intricate fabric of archetypal structures. These archetypes are anchored in their underlying eternal truths that are identified by ever-changing phenomena.

Crucially, the ability to differentiate the ego from the identity—termed Viveka12 in yoga teachings—plays a pivotal role. It allows individuals to disengage from the events of life and become grounded in their existential reality.

According to the teachings of ancient Eastern wisdom, this profound revelation—the separation of self-truth from life experiences—can only be attained through enstasy. During moments of enstasy, the “I” undergoes a process of annihilation, shedding the ego. In these transcendent moments, the dichotomy between subject and object dissolves, permitting individuals to establish themselves in their truth. In the absence of the ego, the entity of objects loses its substance. Enstasy enables individuals to unite with the most abstract dreams embedded within their objects, embracing the profound wholeness inherent in themselves—a state characterized by peace, happiness, and blessings.

While the theme of enstasy may appear abstract, it remains deeply ingrained in the realm of human experiences. Certain moments in human existence offer glimpses of a temporary loss of ego—an escape from the confines of self-consciousness. These instances, though rare, are not unfamiliar. For instance, when individuals become enraptured by breathtaking landscapes, exquisite art, or transcendent music, they momentarily disconnect from their egos. In these moments, they establish a connection with pure beauty devoid of knowledge, information, ego-driven needs, or mechanisms. It is during these instances that the most profound contentment is experienced.

Yet, is it conceivable that we may find fascination in our true identity, unlocking a sense of peace and profound inner happiness—unrelated to external beauty or scientific facts? Eastern mysticism refers to such states as enstasy, marking the initiation of a journey into the inner world of human existence. These spiritual traditions contend that genuine inner peace and happiness remain elusive as long as the multiplicity of subjects and objects, coupled with the duality between them, prevails. It is solely through enstasy that individuals can attain a state of inner contentment.

The nature of the experience born from these ecstatic states is indescribable in words. Nevertheless, we are all familiar with moments of enchantment with beauty—well-known experiences marked by the absence of ego, often accompanied by the most creative and inspiring insights. It is within these states of enstasy and egolessness that many artists and scientists have crafted enduring masterpieces. Although these visionaries achieved this state by immersing themselves in the beauty of the world or the pursuit of scientific truths, the wisdom of Oriental mystics suggests that individuals can venture even further, delving into the depths of their existence by becoming enraptured with their true inner selves.

X. The Eternal Quest for Meaning

As we conclude this exploration of Eastern philosophy’s profound insights into the philosophy of life and its meaning, we find ourselves at the crossroads of existence. Eastern wisdom invites us to embark on an inner odyssey, transcending the temporal and material pursuits that often define our lives in the modern world.

We have delved deep into the dichotomy of subject and object, understanding how the interaction between the two infuses life with meaning and motivation. We’ve explored the intricate tapestry of human experiences, recognizing the ever-changing nature of existence and the absence of a fixed identity. In this journey, we’ve confronted the concept of suffering, stemming from ignorance, ego, attachment, aversion, and the innate will to live.

However, Eastern philosophy doesn’t leave us mired in the complexities of suffering but offers a path toward liberation. The concept of enstasy, the suspension of the ego’s identification with external objects, provides moments of profound detachment and oneness with our intrinsic truth. These moments of inner happiness and peace serve as a beacon, guiding us toward a more meaningful and fulfilling existence.

In our pursuit of meaning, we must remember that this quest is not a destination but a continuous journey. Eastern wisdom encourages us to cultivate mindfulness, self-awareness, and a deep connection with our inner selves. It reminds us that the path to meaning is not found in the accumulation of material wealth or external achievements but in the exploration of our inner landscapes and the realization of our true selves.

As we navigate the complexities of life, Eastern philosophy offers a timeless message: the search for meaning is an eternal quest, and its discovery lies within the depths of our consciousness. By understanding the interplay of subject and object, by transcending the ego, and by experiencing moments of enstasy, we can find glimpses of the profound meaning that underlies all of existence.

In the grand tapestry of human history, the philosophy of life and its meaning remains an enigma waiting to be unraveled. Eastern philosophy, with its rich traditions and profound insights, continues to be a source of inspiration and guidance on this timeless journey. It reminds us that, ultimately, the meaning of life is a deeply personal and inner exploration, and the wisdom to uncover it lies within each of us.

As we conclude our philosophical odyssey through the lens of Eastern wisdom, let us embrace the wisdom of the sages and embark on our quest for meaning, knowing that the path is as important as the destination and that in the depths of our consciousness, we may discover the profound meaning we seek.

References:

- Chittick, William C. (1994) Rumi and Wahdat al-Wujud. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Mainkar, T. G. (2004) Samkhyakarika of Isvarakrsna: With the Commentary of Gaudapada. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthan.

- Ballantyne, James R. (2003) Sankhya Aphorisms of Kapila with Extracts from Vijnanabhiksus Commentary. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Sovani, V. V. (2005) A Critical Study of the Sankhya System: On the Line the Sankhya-Karika, Sankhya-Sutra and their Commentaries) Chaukhamba Vidya Bhawan.

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (2002) Prakrti in Samkhya-Yoga: Material Principle, Religious Experience, Ethical Implications. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- Larson, Gerald James. (2001) Classical Samkhya: an Interpretation of Its History and Meaning. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Ganganath Jha, Mahamahopadhyaya. (2004) The Samkhya-Tattva-Kaumudi: Vacaspati Misra’s Commentary on the Samkhya-karika. Chaukhamba Vidya Bhawan, Varanasi.

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli. (1953) The Principle Upanishad. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- Woodroffe, Sir John. (1975) Shakti & Shakta. Madras, India: Ganesh & Co.

- Dasgupta, Surendranath. The history of Indian Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 1952 – 55. 5 Vols.

- Chittick, William C. Imaginal worlds: Ibn al-ʿArabī and the problem of religious diversity. State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Feuerstein, Georg A. The Yoga-sūtra of Patañjali: A new translation and commentary. Rochester, Vt. : Inner Traditions, 1989.

- Vireswarananda, Swami. Brahma-Sutras: With Text, Word-For-Word Translation, English Rendering, Comments According to the Commentary of Sri Sankara and Index. Advaita Ashrama, 2001.

- Sharma, Arvind. Advaita Vedānta: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, 2004.